Human Origins: 3D Models

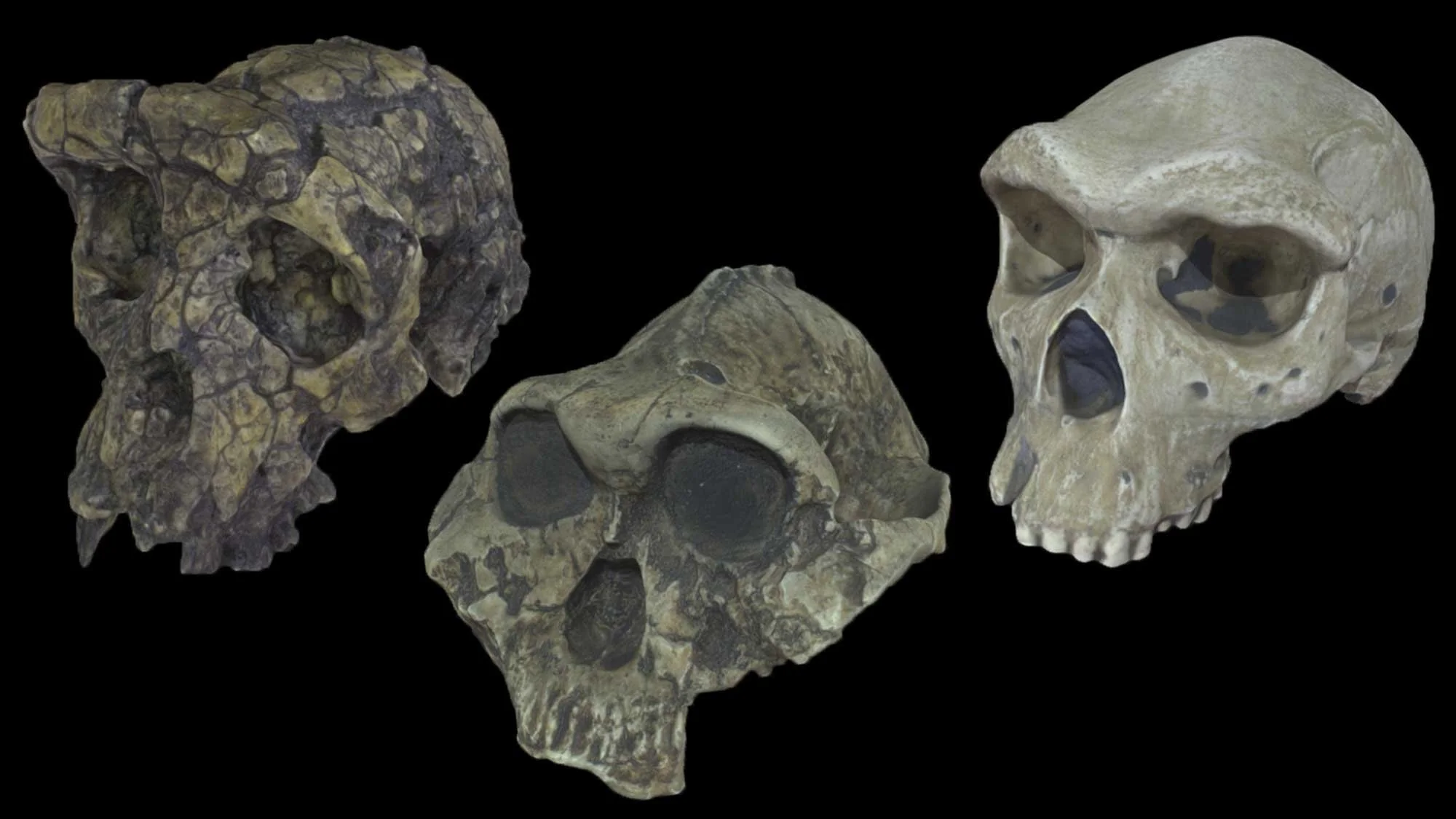

Explore adaptive changes in hominin skulls for yourself by experimenting with our Virtual Collection of 3D photogrammetry models.

These 3D models were created by Hannah Teush using casts of specimens at Cornell University. Information about individual species is adapted from the Smithsonian’s Human Origins website and the Australian Museum’s Human Evolution website with editorial assistance from Ryan McRae, George Washington University.

Sahelanthropus

Sahelanthropus tchadensis

Where: West-Central Africa (Chad)

When: 7.2 million to 6.8 million years ago

Locomotion: The foramen magnum, the hole where the spinal cord exits the cranium, is located further forward and more directly under the cranium than in modern apes, but less so than in species of the genus Homo, suggesting that Sahelanthropus held its body upright. Whether this means it also walked bipedally is debated, although recently described arm bones indicate arboreal climbing was still important for this species.

Diet: Teeth are not well preserved, and so studies of them are incomplete. This leaves paleoanthropologists to make educated guesses of Sahelanthropus’ diet, based on known environment and studies of similar species: predominantly plant-based; featuring fruit, roots, nuts, and leaves.

Other facts: Sahelanthropus tchadensis is one of the few early hominins found outside of Eastern and Southern Africa. Its retention of predominantly ape-like features led some scientists to suggest it may not actually be a hominin at all, or may exist too close to the chimpanzee-hominin evolutionary split to be placed in either lineage confidently.

Ardipithecus

Ardipithecus ramidus

Where: Eastern Africa (Ethiopia)

When: 4.51 million to 4.3 million years ago

Locomotion: Skeletal remains indicate a divergent large toe, similar to modern apes, combined with a rigid foot, a more human feature. This along with a vertically positioned foramen magnum (where the spinal cord exits the skull) and a presumably bipedal-looking hip indicate that this species walked on two legs, although likely in a different way than modern humans do. Long arms and ape-like shoulders indicate it also spent a lot of time climbing arboreally.

Diet: Teeth indicate an omnivorous diet, with enamel thickness intermediate between that of modern chimpanzees and Homo sapiens, although living in a wooded environment it likely relied heavily on fruit.

Other facts: Other animal remains found alongside Ar. ramidus indicate that it lived in a wooded environment, which seems to contradict the popular “savanna theory” – that bipedalism emerged as a response to the environment changing from forest to grassland. Its mix of ape-like and human-like features also indicate that bipeal locomotion may have been the first “human-like” adaptation in our lineage.

Australopithecus

Australopithecus afarensis

Where: Eastern Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania)

When: 3.7 million to 3.0 million years

Locomotion: With hips, legs, and feet all adapted for bipedal walking this species surely spent a lot of time on two feet. However, its arms and shoulders were still structured to assist in arboreal climbing, although the extent to which this species remained arboreal is debated.

Diet: Tooth shape and microwear suggest a predominantly plant-based diet.

Other facts: This is one of the more universally recognized early human species thanks in part to “Lucy”, a relatively complete skeleton discovered in 1974. Another notable find is the “first family” from Hadar, Ethiopia, a collection of skeletons both male and female of all ages. The cranium depicted in the model here is a composite image, representing an average specimen derived from multiple male crania.

Australopithecus africanus

Where: Southern Africa

When: 3.0 million to 2.4 million years ago

Locomotion: Hip and ankle joints indicate habitual bipedal locomotion, but curved fingers, long arms, and shrugging shoulders are somewhat more ape-like. This suggests that Au. africanus could have spent at least part of its time in the trees. It is also possible, that these traits were simply inherited from an earlier tree-living ancestor, much like the retention of tail bones in modern day humans.

Diet: Tooth shape and wear suggest Au. africanus had an omnivorous diet similar to modern chimpanzees.

Other facts: The “Taung Child,” a young Au. africanus individual found in 1924 in South Africa, established that early hominin fossils occurred in Africa long before they did in Europe. It took another 20 years after the discovery for the predominantly European scientific community to accept that human ancestors originated in Africa, an idea first suggested in the 1870s by Charles Darwin.

Paranthropus

Paranthropus boisei

Where: Eastern Africa

When: 2.3 to 1.2million years ago

Locomotion: Paranthropus boisei retains all the characteristics of bipedal locomotion present in earlier hominins, although less flexibility in the ankle joint may indicate that it moved bipedally in a somewhat different manner.

Diet: Thick tooth enamel, large cheek bones, and a large sagittal crest on the head all indicate large and strong chewing muscles. Accompanied by proportionally massive molars and premolars, this species likely was adapted to eating fibrous foods that were tough to chew, although tooth wear studies suggest a mixed diet of both softer and harder, abrasive foods.

Other facts: Overall body size was small compared to modern humans, with the males of the species averaging just over four feet tall. Despite another species being named “robustus,” P. boisei is actually the most robust of the Paranthropus species, the other two being P. aethiopicus from eastern Africa and P. robustus from southern Africa. This genus collectively represents an evolutionary offshoot in the hominin lineage, of which no species survived to the present day.

Homo

Homo habilis

Where: Eastern and Southern Africa

When: 2.35 million to 1.65 million years ago

Locomotion: Foot, leg, and pelvis structure indicates that H. habilis was predominately bipedal.

Diet: Dental analysis suggests that H. habilis ate tough leaves and woody plants, along with some meat.

Other facts: Found in sites where stone tools of the Oldowan industry were also discovered, H. habilis may have been one of the first species to regularly utilize stone tool technologies. “Homo habilis” in Latin roughly translates to “handy man.” H. habilis is named in the same genus as modern humans more for its association with stone tools despite its brain size not being much different from contemporary and earlier Australopithecus fossils. Oldowan tools are also found in the same sites as another hominin species, Paranthropus boisei, leaving it unclear which of these species, or both, created the tools.

Homo erectus

Where: Northern, Eastern, and Southern Africa; West and Eastern Asia

When: 1.81 million to 110,000 years ago

Locomotion: Although earlier species of hominins engaged in habitual bipedal walking, Homo erectus is the first to definitively walk obligately on two legs in the same way that modern humans do. Bipedal walking freed up hands for gathering food and carrying tools, and it allowed H. erectus to be taller and able to walk long distances.

Diet: Some of the earliest evidence for control of fire and more complex stone tools from the Acheulean industry appear in the archaeological record at the same time as H. erectus. Previously, it was thought that consuming more meat led to increased brain sizes in this species, but recent studies indicate that while H. erectus certainly consumed meat, there was no dramatic increase corresponding to this species’ emergence.

Other facts: H. erectus was highly varied in body shape and widely distributed geographically, being found in both Africa and Asia. This variety has led some paleoanthropologists to distinguish the African and Asian individuals as separate species, H. erectus (found on the Asian continent) and H. ergaster (found on the African continent).

Much of what we infer about this species comes from one complete skeleton, “Turkana Boy” from Western Kenya.

Homo ergaster

Where: Eastern, Southern, and Northern Africa

When: 1.7 million to 1.4 million years ago

Locomotion: Relatively long legs and shorter arms, closer in proportion to modern humans than earlier ape-like relatives, indicates habitual bipedal locomotion in the same way that modern humans move.

Diet: A smaller gut and larger brain than its earlier ancestors suggests that H. ergaster ate and required more nourishing foods. This likely included incorporation of meat, cooked foods, and underground tubers, all of which required tools to access and process.

Other facts: Originally referred to as African Homo erectus, some paleoanthropologists suggest that H. ergasterand H. erectus are actually two different species. Although H. ergaster is the temporally earlier species, the first fossils that were found belonged to H. erectus in Java, Indonesia in 1891 meaning that Asian fossils would belong to H. erectusand African fossils to H. ergaster if they are split into two species. Whether these fossils collectively represent one, two, or more species is a current topic of debate in the paleoanthropological community.

Homo floresiensis

Where: Indonesia

When: 100,000 to 50,000 years ago

Locomotion: Homo floresiensis’ pelvis, knee, and foot structure indicate habitual bipedal locomotion, although its legs were shorter and its feet were proportionally longer than modern humans.

Diet: The archaeological record suggests that Homo floresiensis was a prolific user of stone tools. There is also evidence that H. floresiensis selectively hunted Stegodon, an extinct pygmy elephant, among other prey species.

Other facts: Homo floresiensis was remarkably small relative to other Homo species standing just over a meter, about 3 feet tall, along with large feet which has earned it the nickname “The Hobbit”. Remains of this species are only found on the Indonesian island of Flores. Homo floresiensis also has a proportionally smaller brain than other late surviving hominins being smaller in size than a modern chimpanzee. It has been suggested that the small size of H. floresiensis is due to a evolutionary phenomenon known as island dwarfism, a result of being isolated in an environment with limited food resources, as well as few predators.

Homo heidelbergensis

Where: Europe, Africa, possibly Asia

When: 700,000 to 100,000 years ago

Locomotion: Homo heidelbergensis, with a skeleton similar to H. sapiens and other closely related species, was obligately bipedal.

Diet: Animal remains with butchery marks found at H. heidelbergensis sites suggests that they were capable of hunting larger animals. They likely relied on smaller animals and plant foods as well.

Other facts: Primitive hearths, fire altered tools, and burnt wood found at H. heidelbergensis sites suggest that it was capable of using fire. There is also evidence at a site in Spain of intentional burial, either for sanitary or cultural purposes.

The late Pleistocene species of Homo found in Africa, Europe, and Asia contribute to the “muddle in the middle,” a period of time in which scientists disagree how many species of hominins existed and which, if any, were ancestors to later species like Neanderthals, Denisovans, and H. sapiens.

Homo neanderthalensis

Where: Europe, Near East, and southwestern to central Asia

When: 400,000 to 40,000 years ago

Locomotion: Fully bipedal walking and running as in modern humans

Diet: Adapted to living in colder environments than African hominin species, H. neanderthalensis, known as "Neanderthals", had a seasonal and varied diet. Nitrogen isotope data suggests this species may have been hyper-carnivorous, although it is likely they heavily relied on plant-based foods as well.

Other facts: Neanderthals were physically well-adapted for the colder environments of Europe and western Asia, with their stocky builds, barrel-shaped chests, and large nasal cavities indicating big noses for humidifying and warming cold air. Neanderthals are modern humans' closest extinct relatives. They used many tools, made clothing, and controlled fire. They even had an average brain size slightly larger than modern humans, although their brains were differently shaped. Early Homo sapiens overlapped with Neanderthals in many places in Europe and Asia with evidence of interbreeding between the two present in the genomes of most modern humans alive today.

Modern Homo sapiens

Where: Originated in Africa, now spread across the entire world

When: 300,000 years ago to today

Locomotion: The skeleton of Homo sapiens is built for fully bipedal activities, perhaps specifically for distance running. The arms and shoulders of H. sapiens do not allow efficient arboreal climbing as in other ape species and earlier hominins.

Diet: When modern humans arose in Africa, they subsisted as hunter-gatherers. Around 12,000 years ago some humans began to cultivate specific plants and animals, turning to a more sedentary lifestyle, although many modern human groups still practice hunting and gathering.

Other facts: While modern human brains are proportionally the largest among all animals, second only to Neanderthals, it is primarily an expanded frontal lobe that gives H. sapiens the capacity for complex thought. Although Neanderthals shared many cultural traits in common, H. sapiens is currently the only known species to produce complex art.

Homo sapiens has co-existed in time, perhaps in the same place, with several other species of Homo including Homo erectus, H. neanderthalensis and the Denisovans, with Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA being present in the genome of some modern humans as a result of interbreeding. Smaller-brained H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis from Indonesia and the Philippines, respectively, may have been the last hominins surviving other than H. sapiens as late as 17,000 years ago.