Cnidarians

Cnidarians

Cnidarians (pronounced “ni-dare-ians”) are a group of animals that includes jellyfish, sea anemones, corals, and other animals. All cnidarians use harpoon-like stinging cells on tentacles to capture their prey. Because of their hard exoskeletons, corals have an excellent fossil record. This is not the case for soft-bodied cnidarians, which have a very poor fossil record. Surprisingly, however, soft-bodied cnidarians are known from the Devonian fossil record of New York State! Fossils of the feather-shaped hydrozoan Plumalina are sometimes encountered on slabs of Ithaca Formation shale and an example is shared below.

The hydrozoan Plumalina sp. from the Upper Devonian of Steuben County (PRI 80134).

Corals

Some species of modern corals are very important ecosystem engineers because their hard exoskeletons build vast reefs over time that other animals depend upon for habitat. In comparison, the individual animals that build reefs are usually very small and look like tiny sea anemones. All modern corals belong to a group called scleractinians (pronounced “sklair-ac-tin-ians”). This group did not evolve until the Triassic Period, more than 100 million years after the end of the Devonian. Devonian corals are assigned to two groups that are now extinct: rugose corals and tabulate corals. Unlike rugose corals, all tabulate corals were colonial.

Tabulate Corals

Some tabulate corals grew on top of the shells or exoskeletons of other animals and are called “encrusters.” Other tabulate corals grew forms that have a strong resemblance to the honeycombs constructed by modern bees. For that reason they are called “honeycomb corals.”

Examples of Devonian tabulate corals from New York

Rugose Corals and Days Per Year During the Devonian

Rugose corals are commonly called “horn corals” because solitary individuals sometimes look like the horn of a bull (they are sometimes also mistaken for large teeth!). Some species of rugose corals, however, formed dense colonies composed of numerous individuals. Both types are found in Devonian rocks in New York, though solitary forms tend to be more common.

Examples of Devonian rugose corals from New York

Research on solitary rugose coral fossils from New York and elsewhere by Cornell professor John Wells during the 1960s led to a remarkable discovery about Earth’s history. Wells used rugose corals to address the question of how many days per year there were in the geological past. From his research, Wells knew that modern corals grow just a little bit every day, leaving behind a fine, visible growth line. He also knew that modern corals often produced thickened growth bands once per year, possibly due to changes in seasonal water temperatures. When he counted the number of daily growth lines between the thicker, yearly bands on the modern corals, he predictably counted almost 365 lines (i.e., nearly one per day).

Heliophyllum halli from the Middle Devonian Moscow Fm. of Erie County, New York (PRI 70755). This is one of the genera of rugose corals studied by Wells, though is not one of his specimens. Insets show details of fine growth lines (likely not daily growth lines, however) and possible annual banding.

What about the number of daily growth lines in Paleozoic rugose corals, which show the same sorts of thickened annual bands? When Wells counted the daily growth lines per annual cycle on Middle Devonian rugose corals, he counted 385 to 410 growth lines (400 was typical). Pennsylvanian corals showed 385 to 390 lines.

Thus, Wells corroborated—using simple observations of specimens of fossil corals—the finding of physicists that Earth’s rate of rotation has slowed over time. Days were shorter during the Devonian Period! His results suggest that there were ~400 days/year during the Devonian and ~390 days/year during the Carboniferous Period. Over time, the Earth’s rate of rotation has continued to decrease—albeit at a very, very slow pace—and this trend will continue for millions of years to come. The slowing itself is mostly due to the friction that the Moon’s gravity exerts upon the Earth, which results in tides.

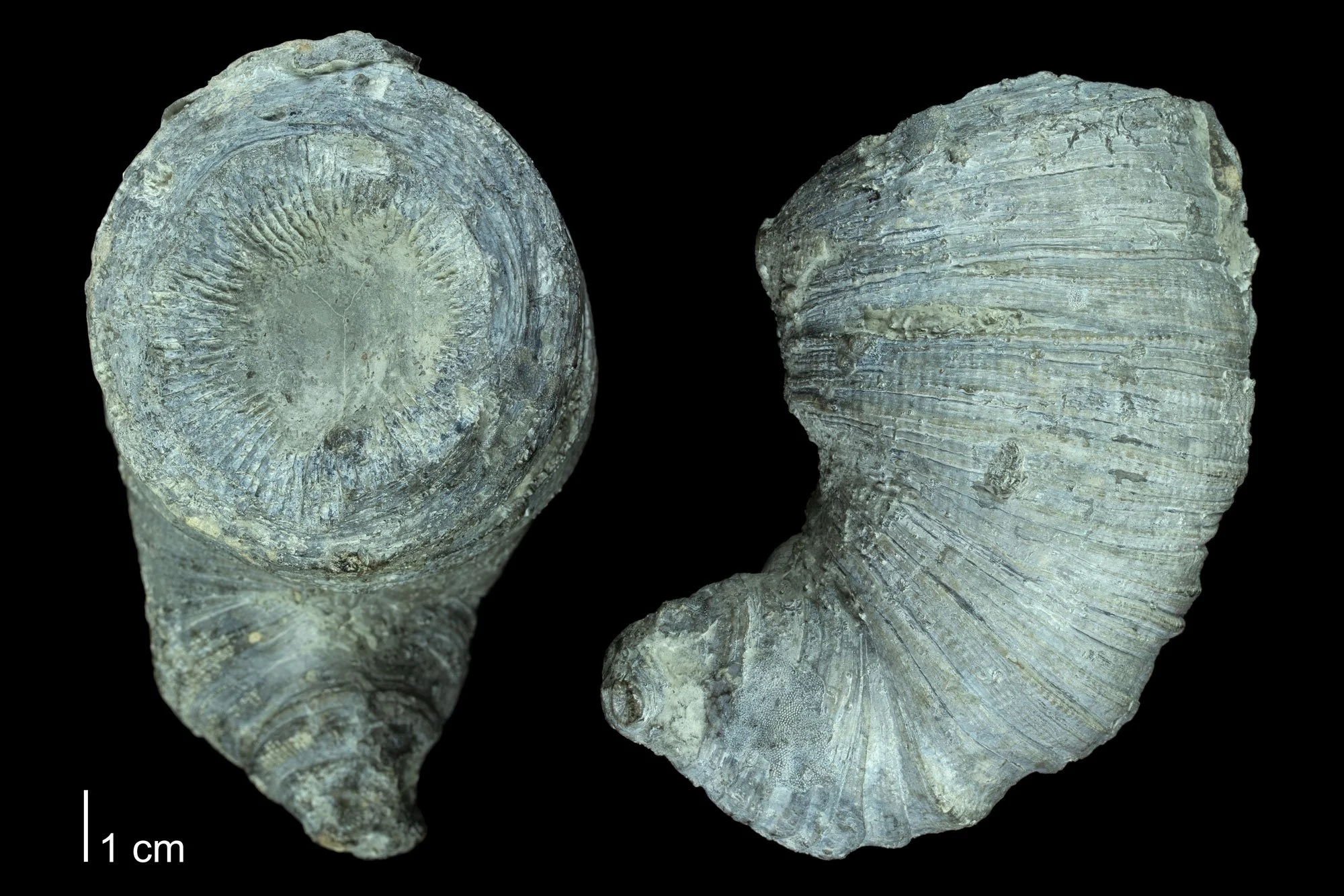

Devonian rugose coral specimens that were studied by John Wells as part of his investigation of the Earth’s rate of rotation during the Devonian Period. Left: Heliphyllum sp., Ludlowville Formation, Genesee County, New York (PRI 83105). Right: Eridophyllum archiaci, Moscow Formation, Livingston County (PRI83106). Can you identify the types of growth lines that were studied by Wells? See 3D models of these specimens below.