Pre-Devonian

Introduction to New York Before the Devonian Period

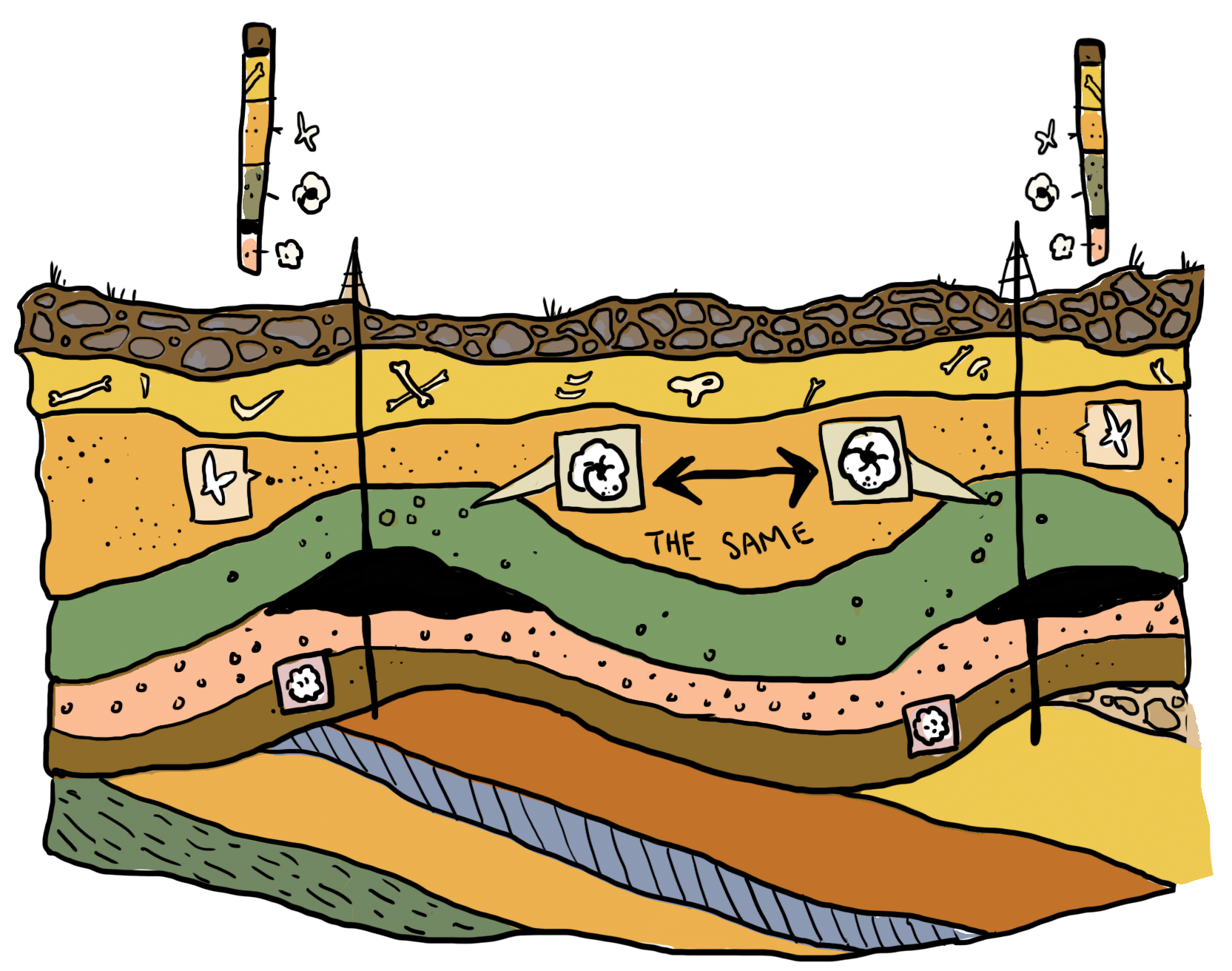

Most of Central and Western New York’s geology has “layer cake stratigraphy.” The youngest rock layers in Central and Western New York are from the Devonian, mostly at high elevations. Older rocks from the Cambrian, Ordovician, and Silurian are found only in low-lying areas in the northern half of Upstate New York. These older rocks are also found in deep mines and holes, under Devonian bedrock.

CUBO drill site at Cornell University.

CUBO mud logger, Juliette Torres (CALS ‘23) takes samples of rock chips from the drill site for geological evaluation.

Cornell University Borehole Observatory (CUBO)

Different rock layers, each representing a different time in geological history, come to the surface in different parts of New York due to topography and slight tilting of the layers southward (toward Pennsylvania). To study the whole Devonian Period and older rocks, we can travel to rocks in different parts of New York State. We can see all the rocks in one place, however, if we drill a deep hole.

A borehole nearly two miles deep was drilled on the Cornell University campus in summer 2022 to research whether Cornell might be able to heat its campus using the heat from the interior of the Earth, an idea known as “Earth Source Heat.” The hole that was drilled is known as the Cornell University Borehole Observatory (CUBO). It cut through sedimentary layers from Devonian rocks at the surface down through rocks from preceding geological periods (Silurian, Ordovician, and Cambrian) and then ultimately into the ancient, crystalline “basement” rock of the Proterozoic, which is more than 541 million years old.

Relief map of New York (USGS)

Generalized stratigraphy below the Cornell Borehole Observatory in Ithaca, New York (red dot).

Proterozoic Basement

Oldest Rocks in New York

The oldest rocks in New York are from the Proterozoic Eon, a vast interval of time that began 2.5 billion years ago and ended at the start of the Cambrian Period, 541 million years ago. Earth’s Proterozoic ocean teemed with single celled bacteria and algae. Multicellular life first appeared at the very end of the Proterozoic.

Proterozoic-aged rocks are mostly crystalline (sometimes referred to by geologists as “hard” rocks). Unlike the softer sedimentary (“soft”) rocks (sandstones, siltstones, shales, and limestones) that dominate New York’s bedrock, these Precambrian rocks are igneous granites and highly altered metamorphic rocks that reflect New York’s tectonically active ancient history.

Proterozoic rocks lie deep beneath your feet right now, but the best place to see them in New York is the Adirondacks!

Simplified illustration of the rock cycle, which explains how existing rocks change into other kinds of rocks due to heat and pressure.

How Did These Rocks Wind Up On The Surface?

About 10 million years ago, volcanic activity began to uplift the Adirondack region. The deepest, oldest metamorphic rocks were punched upwards through the younger overlying rocks, opening a window into Earth’s history from nearly 2 billion years ago.

Precambrian metamorphic rocks of the Marcy Anorthosite, Jay Dome, Adirondack Mountains, New York. Photo courtesy of James St. John.

Proterozoic “hard rocks” at the summit of Whiteface Mountain in New York. Photograph by “daveynin” (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Cambrian Period (541-485 million years ago)

Lester Park, Saratoga Springs, New York.

Cambrian rocks skirt the north and south sides of the Adirondacks and are also found in eastern New York. One of the best places to visit Cambrian rocks up close is near Saratoga Springs, where you can explore stromatolite fossils.

Stromatolites are layered, mound-shaped structures built by slimy photosynthetic bacteria. Sediment sticks to the slime, building up hard and rocky layers over time. The result looks something like a cabbage, although stromatolites are not related to plants.

Stromatolites still form in oceans today, but they are very rare. They are only found in habitats without grazing animals like snails that love to eat the slime. There were many more stromatolites during the Precambrian, long before the first animals evolved. Stromatolites provide the oldest evidence for life on Earth. Some stromatolite fossils from Australia are about 3.5 billion years old!

The 490-million-year-old Cambrian stromatolite fossils found near Saratoga Springs are much younger than these oldest-known fossils, but are still 70 million years older than the first Devonian fossils. They lived in shallow, sunlit ocean water, which allowed the photosynthetic cyanobacteria to flourish. You can visit the stromatolites for free at Lester Park, west of Saratoga Springs! The stromatolites at Lester Park were the first described in North America and remain a valuable teaching aid for college and university classes nationwide. Look and learn, but collecting is not allowed at Lester Park!

Ordovician Period (485-444 million years ago)

Trenton Falls near Utica, New York, 1873.

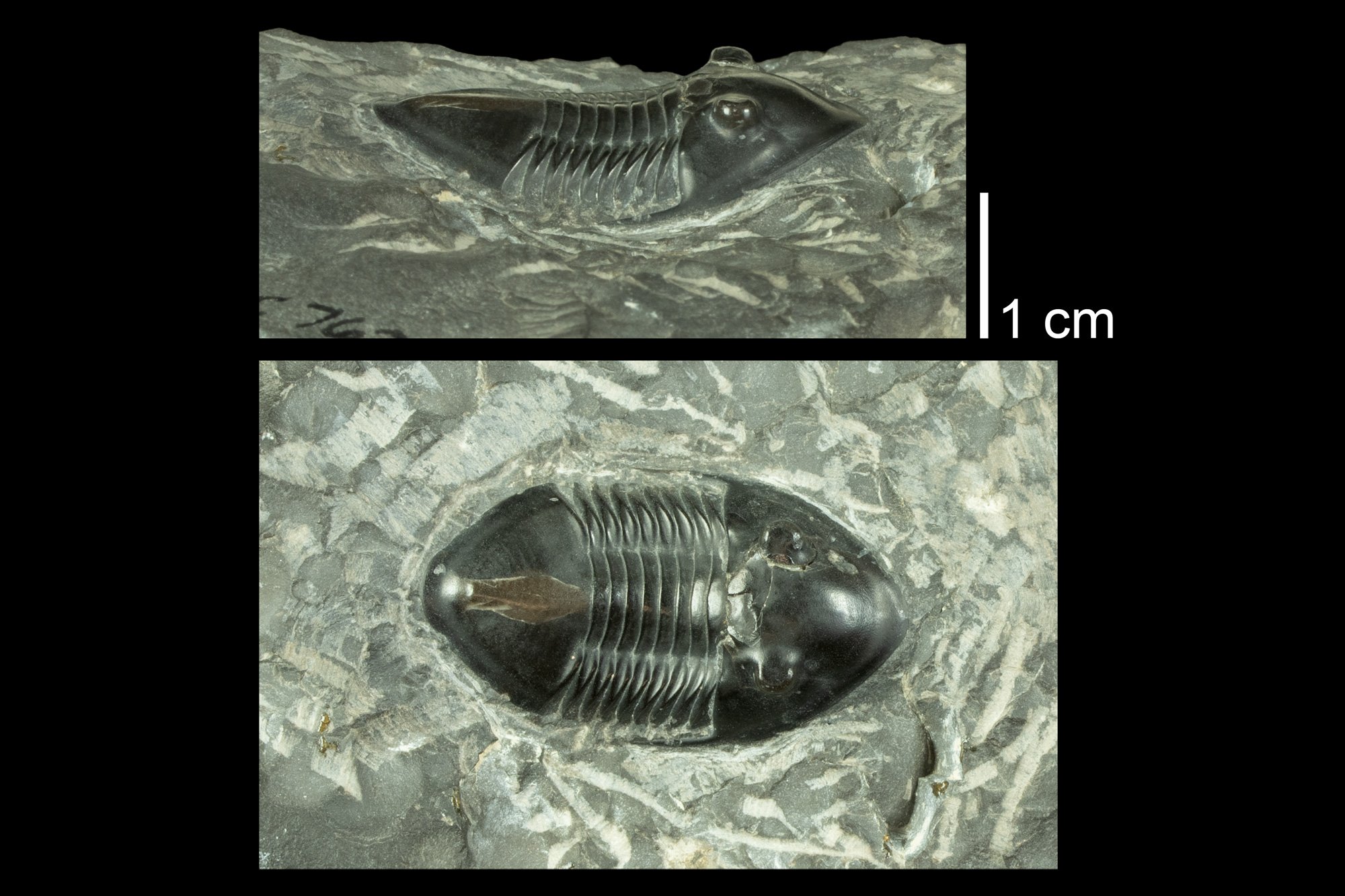

Ordovician rocks are exposed in northern and eastern New York State and give us a good look at trilobite fossils. Trilobites are an extinct group of arthropods, and were relatives of modern animals like horseshoe crabs, spiders, and scorpions. Their name comes from the three lobes of the central region of their bodies (tri-lobe-ites). Trilobites are common fossils in Cambrian- to Devonian-aged rocks. They became less common after the Devonian before going completely extinct at the end of the Paleozoic.

Trilobites from near Trenton Falls, New York

Ordovician trilobite fossils from the Trenton Group of rocks near Trenton, New York have received considerable attention from paleontologists for over a century.

Take Isotelus home today!

The Isotelus trilobite is the state fossil of Ohio, and trilobites of this genus are the largest in the world. Some reached over two feet in length! They lived during the Ordovician Period, between 480 and 430 million years ago.

Trilobites from the Walcott-Rust Quarry

Limestone at the Walcott-Rust Quarry.

Some of the most famous Trenton Group fossils from New York come from the Walcott-Rust Quarry. The quarry is named for its discoverers: Charles D. Walcott (1850–1927) and William P. Rust (1826–1897). Walcott was especiall interested in the trilobite fossils because of how well they are preserved at this location. These were the first fossils to show the anatomy of trilobite legs and gills.

Many decades later, Rochester-based avocational paleontologist Thomas Whiteley re-excavated the Walcott-Rust Quarry and developed significant new collections, most of which are now housed at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University and the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University. PRI has a small collection of specimens from this quarry, one of which is displayed here.

Trilobite Ceraurus pleurexanthemus from the Ordovician Rust Member of the Trenton Group, Walcott-Rust Quarry, Herkimer County, New York (PRI 42094).

Beecher’s Trilobite Bed

Beecher’s Trilobite Bed is a thin layer of Ordovician shale located in Oneida County, New York. It is best known for its preservation of complete trilobite specimens with soft body parts that are not typically fossilized. These parts include delicate limbs, gills, antennae, and more. Remarkably, these soft parts are preserved as pyrite, or fool’s gold. These trilobites were first studied in detail more than a century ago by Charles Beecher of Yale University, whose name subsequently became associated with the locality.

Most of the trilobite specimens at Beecher’s Trilobite Bed belong to one species, Triarthrus eatoni. Cornell Professor Emeritus John Cisne investigated the anatomy of this species in detail. His research was published by the Paleontological Research Institution in 1981.

Explore the world of the Ordovician Period.

Join our friends from the Ordovician Period for an exciting adventure through time! Get ready to explore prehistoric reefs and meet crazy creatures. Nautiloids, trilobites, and jawless fish... who will survive the first big mass extinction?

Silurian Period (444 to 419 million years ago)

Silurian rocks are found in the northern parts of Western New York, the Finger Lakes, and Central New York. Their best exposure is at Niagara Falls. The Niagara Escarpment is made up of hard dolostone that formed from small bits of shells and corals that accumulated in warm, shallow ocean water during the Silurian Period. The Niagara Escarpment outcrops from near Rochester to the thumb-shaped Door Peninsula of Wisconsin.

Niagara Escarpment shown in red.

Cayuga Salt Mine

As seawater evaporated during the Silurian Period, it left behind one of the Finger Lakes’ most important natural resources: a thick layer of salt! The Cayuga Salt Mine, which is located about 2,000 feet below the surface, has been operated by the Cargill Corporation since 1970. About two million tons of salt are excavated annually from beneath Cayuga Lake. Most of this salt is used to de-ice roads in New York and the northeastern United States during the winter. A large chunk of this salt can be viewed in our permanent exhibits.

Fold in Silurian salt beds in the Cayuga Salt Mine (Cargill Inc.) in Lansing, New York, about 2000 feet underground. Deeper salt beds are less deformed and, although 15 feet or less in thickness, are more efficiently mined. (Photo by Art Bloom; published by PRI in Gorges History).

New York’s Official State Fossil: Sea Scorpion Eurypterus remipes

Model of the eurypterid (sea scorpion) Eurypterus remipes, New York’s official state fossil.

New York’s official state fossil, the eurypterid Eurypterus remipes, lived during the Silurian. Eurypterids are also known as “sea scorpions,” though they were not closely related to the scorpions that live on land today. Fossils of Eurypterus remipes are common in some deposits of New York’s Silurian Bertie Limestone exposed in Herkimer and Oneida counties.

Eurypterids lived in shallow water and may have spent short amounts of time on the shore. As arthropods, they had to molt their hardened shell (exoskeleton) to grow (this was also true for trilobites). As a result, a single eurypterid could leave behind many pieces of exoskeleton. Many eurypterid fossils represent these molts. Complete specimens are much rarer.

Smithsonian Eurypterid Diorama

The eurypterid diorama shown below was created in 1980 and exhibited at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History for many years. Although some details have been revised since the 1980s, most paleontologists who specialize in these fossils agree that this diorama is still basically accurate. The below is an interactive 3D model of this diorama. Click on the arrow to load and explore the diorama by scrolling and zooming in with your mouse. Search the diorama for the eurypterids Eurypterus, Pterygotus, Hughmilleria, a centipede (one of the earliest land animals), and Cooksonia, one of the first land plants.

Giant Eurypterid!

There were several different major types of eurypterids and a range of sizes. Although most eurypterids were less than 1 to 2 feet long, others were among the largest invertebrate animals that have ever lived. The largest eurypterids reached lengths of more than 8 feet. The world’s single largest complete fossil specimen of a eurypterid–Acutiramus macrophthalmus (PRI 42897), measuring 49.5 inches long–is on display in the permanent exhibits at the Museum of the Earth (learn more about this specimen in this open access article by Briggs and Roach, 2020 in Geology Today).

Specimen of the giant eurypterid Acutiramus macrophthalmus on display at the Museum of the Earth. Image modified from fig. 9 in Briggs and Roach (2020 in Geology Today).

Take a Eurypterus sea scorpion home!

Eurypterus remipes is New York’s state fossil, and is abundant in certain layers of Silurian-age rocks.

Take a Pterygotus sea scorpion home!

Their many legs had different uses, but the last and largest pair were shaped like paddles, good for swimming about. Some eurypterids, like Pterygotus, also had large claws for catching prey.

Explore the world of the Silurian Period!

Join our friends from the Silurian Period for an exciting adventure through time! Get ready to explore prehistoric reefs and tussle with mighty sea scorpions. What new adaptations will change life on earth forever?